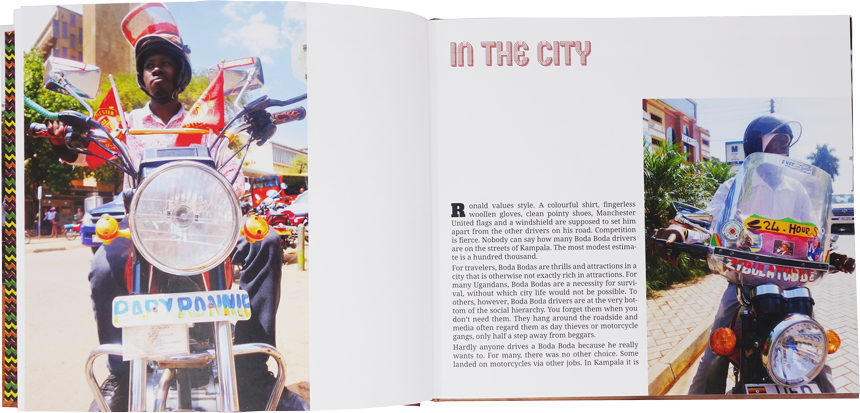

Ronald values style. A colourful shirt, fingerless woollen gloves, clean pointy shoes, Manchester United flags and a windshield are supposed to set him apart from the other drivers on his road. Competition is fierce. Nobody can say how many Boda Boda drivers are on the streets of Kampala. The most modest estimates are a hundred thousand.

For travelers, Boda Boda‘s are thrills and attractions in a city that is otherwise not exactly rich in attractions. For many Ugandans, Boda Bodas are a necessity for survival, without which city life would not be possible. At the same time, however, Boda Boda drivers are at the very bottom of the social hierarchy. You forget them when you don‘t need them, they hang around the roadside like day thieves or motorcycle gangs, they seem only half a step away from beggars.

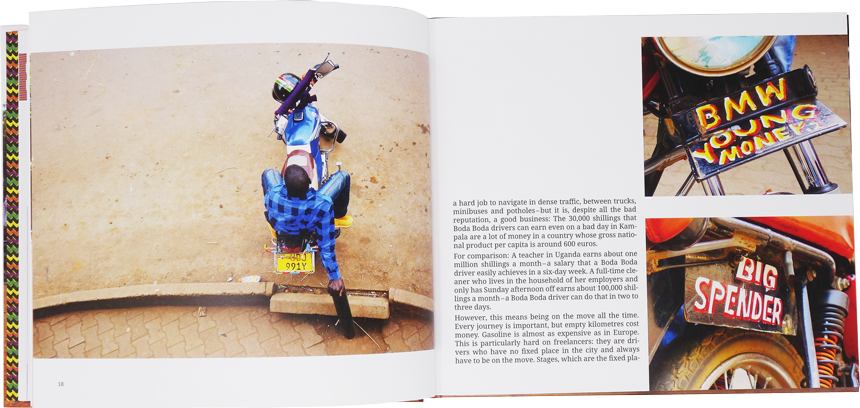

Hardly anyone drives Boda Boda because he really wants to. For many there was no other choice, some landed on motorcycles via other jobs. In Kampala it is a hard job in dense traffic, between trucks, minibuses and potholes – but it is, despite all the bad image, a good business: The 30,000 Shillings that Boda Boda drivers can earn even on a bad day in Kampala are a lot of money in a country whose gross national product per capita is around 600 Euros.

For comparison: A teacher in Uganda earns about one million Shillings a month – a salary that a Boda Boda driver easily achieves with a six-day week. A full-time cleaner who lives in the household of her employers and only has Sunday afternoon off earns about 100,000 shillings a month – a Boda Boda driver can do that in two to three days.

However, this means being on the move all the time. Every journey is important, but empty kilometres cost money. Gasoline is almost as expensive as in Europe. This is particularly hard on freelancers: they are drivers who have no fixed place in the city and always have to be on the move. Stages, which are the fixed places, comparable to taxi ranks, are allocated by associations, trade union-like organisations. Drivers pay membership fees to be admitted to an association, then pay again in Kampala to get a stage seat.

Associations are the only controlling body in the Boda Boda business. And they have become powerful. So powerful that the city administration in Kampala made repeated attempts to push them back. Prohibition zones for Boda Bodas should be introduced with a variety of arguments ranging from a more modern cityscape to air pollution and a high risk of accidents. However, the plans failed because life without motorcycles is simply not possible in Kampala – and finally the president also put his foot down: He declared the city‘s bans invalid. Not least in order to secure the support of this large industry. Today there are only a few »No Boda Boda« signs, especially in villa areas and in front of some shops.

More than a third of the inhabitants of Kampala use Boda Boda several times a day. Apart from the morning and evening trips from the periphery to the city centres, the distances covered are quite short: more than half of them are less than two kilometres. The speed of the Boda Bodas is also not outstanding: In the city centre it is less than ten kilometres per hour, in the suburbs it is only just over twenty. More is not possible in the dense traffic.

These data come from studies at the University of Kampala. Researchers are increasingly discovering the Boda Boda industry as a sociological phenomenon that is being precisely measured and investigated in field research. Their results show: It is love-hate that connects the inhabitants of Kampala with the motorcycles. They are loud, clogging the streets even more – but a life without them is unthinkable. Rival associations often have disputes in the open street, sometimes there are mass fights with Matatu organizations that regard Boda Bodas as hostile competition.